Entail in Tail Male: The Earldom of Salisbury 1337-1428

Posted by: mholford 10 years, 11 months ago

Michael Hicks explores the complicated history of the earldom of Salisbury as revealed in CIPM xxiii.262-85.

These inquisitions relate to Thomas Montagu, earl of Salisbury, who perished at the siege of Orleans on 3 November 1428 without heirs male. [1. A. Curry, ‘Montagu, Thomas (Thomas de Montacute), fourth earl of Salisbury (1388–1428), soldier' , Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, www.oxforddnb.com (subscription required).] They tell the complicated story of where his lands came from – his Montagu, Monthermer, and Grandisson ancestors and Edward III's endowment of the earldom – and explain how the properties were split between his widow, heiress, and heir male. How the present author wishes these inquisitions had been calendared when he first grappled with them forty years ago! Most of Earl Thomas's Montagu and Monthermer lands and those of his first wife Eleanor Holland were inherited by his only daughter Alice, the wife of Richard Neville I. Nine manors were held for life as jointure by Thomas' second wife and widow Alice Chaucer (d. 1475), later duchess of Suffolk, with reversion eventually to her stepdaughter Alice Montagu's line. [2. CIPM xxiii.277, 281; M.A. Hicks, ‘The Neville earldom of Salisbury 1429-71', Richard III and his Rivals: Magnates and their Motives during the Wars of the Roses (London,1991), 356.] A third part entailed in the male line included Christchurch Castle (Hants.), the manor of Canford in Dorset, and other properties in Wiltshire and Somerset worth £230: this was inherited by Thomas' sixty-year old uncle Sir Richard Montagu, son of his grandfather John (d. 1390). [3. CIPM xxiii. 274, 278, 280, 282-3; .Hicks, ‘Neville earldom', 358.] This was insufficient to sustain the earldom of Salisbury, which Richard Neville I was allowed to assume. [4. Hicks, ‘Neville earldom', 355.] Sir Richard Montagu died in 1429 without male heirs. [5. CIPM xxiii.396-8, 425.] Sir Richard's inquisitions correctly identify his nearest kin and heir as his niece Alice, the new countess of Salisbury, who under primogeniture did indeed inherit £19 14s.1¼d rent and two waste watermills from Dartford in Kent, but nothing in Dorset, Gloucestershire, Somerset, and Wiltshire. [6. CIPM xxiii.396-8.] It is a defect of IPMs that jurors characteristically answered the question ‘who was the heir of the deceased?' with the heir by primogeniture whether or not there was anything to inherit or indeed regardless of any entail governing these particular properties. Sir Richard Montagu's IPMs do not explicitly state that in 1429 the properties in Dorset, Somerset and Wiltshire escheated (reverted) to the crown, which the chancery clerks had to establish themselves (as they did), nor of course that King Henry VI subsequently sold them to Cardinal Beaufort. [7. Hicks, ‘Neville earldom', 358-9.] Different parts of Earl Thomas's estate had different heirs. His IPMs enable us to perceive how the process of inheritance and accretion of estates from different sources inevitably meant that families held lands by different titles that had different heirs. This is also a classic case of the operation of entails in the male line.

Inquisitions post mortem are the means that English kings used to track the inheritance of lands held directly of them and to enforce their feudal rights. Almost all these properties were held by knight service and by primogeniture, a set of rules that allowed women to inherit in the absence of direct male heirs. Even though a quarter of peerages failed in the male line every 25 years, as the historian K.B. McFarlane revealed, escheats were extremely rare in the late thirteenth century. [8. K.B. McFarlane, The Nobility of Later Medieval England (Oxford, 1973), 175-6, 251.] This situation changed with the introduction of entails in the male line, which were designed to exclude female heirs. Entails in tail mail were applied to peerages for the first time by Edward III and in due course became the rule for all new peerage titles. This meant that the titles could not pass to females and that such titles and the accompanying endowments often reverted the crown. This was a reason for the large number of creations and extinctions of the peerages in the last two centuries of the middle ages. Another reason, of course, are the periods of internecine strike and plethora of executions. When Edward III first annexed the duchy of Cornwall to the crown in 1337, he made his eldest son Edward, the Black Prince, duke of Cornwall in tail male. Simultaneously he created five new earls in tail male –Gloucester, Northampton, Salisbury, Huntingdon, and Suffolk. Gloucester expired in the male line in 1347, Huntingdon in 1354, Northampton in 1373, Suffolk in 1382, and Salisbury in 1429. [9. Hicks, ‘Neville earldom', 354.] None lasted a century. Derby, a sixth created for life at the same time, was united with the duchy of Lancaster and from 1399 with the crown. That the titles and endowments in tail male were terminated did not mean the end of the families: in each case there were other properties in fee simple that passed to other relatives. Division of estates between heirs male and heirs general were to become quite commonplace, the Arundel and Berkeley estates being notable examples. This was also what would have happened to Warwick the Kingmaker's estates had he died naturally. [10. M.A. Hicks, Warwick the Kingmaker (Oxford, 1998).]

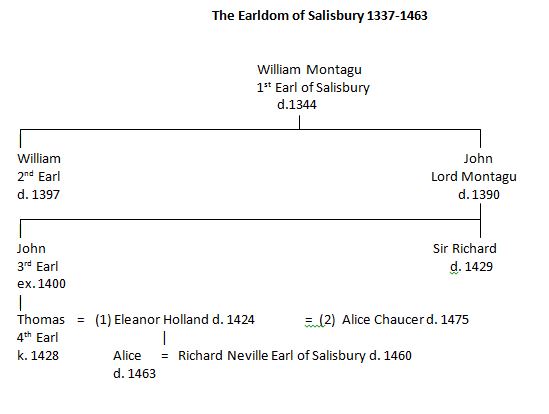

One of these new earldoms was that of Salisbury created for William Montagu I, Lord Montagu, Edward III's favourite, who was endowed to the tune of 2,000 marks a year (£1,333 6s.8d.), including the Isle of Man, the marcher lordship of Denbigh, and the honour, castle, borough, manor and hundred of Christchurch, now in Dorset but then in Hampshire. [11. Fifth Report from the Lords Committee... touching the Dignity of a Peer of the Realm (1829), 26-7; CPR 1334-8, 400, 414-16.] Although he inherited the patronage of the Augustinian priory of Christchurch, he chose to found another Augustinian priory at Bisham in Buckinghamshire, which became the family mausoleum. Depictions appear on both the Salisbury Rolls [of arms], dating from about 1463 and 1483, and which remind us not just of the main line of descent and spouses of each earl, but also the marriages contracted by the earl's daughters and sometimes their cousins. [12. Published in A. Wagner, N. Barker & A. Payne, Medieval Pageant : Writhe's Garter Book : The Ceremony of the Bath and the Earldom of Salisbury Roll, Roxburghe Club (1993); see also A. Payne, ‘The Salisbury Roll of Arms, 1463', England in the Fifteenth Century, ed. D. Williams (Woodbridge, 1987).] The Montagu family consisted of much more than the senior male line of descent. Following his death in 1344, the earldom passed to his son William II (d. 1397), to the latter's nephew John (d. 1400), and to the latter's son Thomas (d. 1428), the last of the Montagu earls. [13. W.M. Ormrod, ‘William Montagu (William de Montacute), first earl of Salisbury (1301–1344), soldier and magnate'; J.L. Leland, ‘William Montagu (William de Montacute), second earl of Salisbury (1328–1397)'; A. Goodman, ‘John Montagu (Montacute), third earl of Salisbury (c.1350–1400), magnate and courtier ‘, Oxford DNB, www.oxforddnb.com.] The fortunes and vicissitudes of the estate can be traced through the inquisitions post mortem of each successive earl and countess. These record additional acquisitions by marriage: Earl John's father had married the heiress of the barony of Monthermer and Earl Thomas married one of the five sisters and heiresses of the Edmund Holland, earl of Kent. [14. CIPM xix.622 ; GEC vii.163.] This was just as well, because the heirs of Earl William I did not retain all that he had been given. Denbigh was recovered by the Mortimer earls of March and Earl William II alienated the Isle of Man. [15. G.A. Holmes, The Estates of the Higher Nobility in the Fourteenth Century (Cambridge, 1956), 27-9.] Earl John suffered forfeiture for treason in 1400 and his son Earl Thomas was only restored to his inheritance in stages. [16. CIPM xxiii.283.] His mother Countess Maud (d. 1424) lost her entitlement to dower: her inquisition post mortem reveals how in 1409 her son Earl Thomas nevertheless provided for her. [17. CIPM xxii.466; see Companion, 34.]

Actually, of course, 1429 is not the end of the story. Alice Montagu's own inheritances by themselves valued at £665 were probably sufficient to support the estate of an earl. [18. Hicks, ‘Neville earldom', 357.] Besides her spouse Richard Neville I (d. 1460) had royal connections. The minority council allowed him to assume the title of earl of Salisbury, in 1442 he secured the third penny of the county of Wiltshire that had reverted to the crown in 1428, and in 1461 his son (Richard Neville II) was able to recover the lands of the 1337 endowment that had been lost in 1428. [19. Ibid. 355, 360-1; A.J. Pollard, ‘Richard Neville, fifth earl of Salisbury (1400–1460), magnate', Oxford DNB, www.oxforddnb.com.] Unfortunately inquisitions post mortem of the Earl Richard I have disappeared since 1828 and there survive no inquisitions for his wife Alice. [20. Calendarium, iv. 296-7, which wrongly identifies him as earl of Shrewsbury.] The earldom passed to their son Richard II (Warwick the Kingmaker d. 1471), to their son-in-law George Duke of Clarence (d. 1478), in 1477 to Richard III's son Edward of Middleham (d. 1484), and to Clarence's daughter Margaret Countess of Salisbury (ex. 1541). [21. Hicks, ‘Neville earldom', 355; Michael Hicks, False, Fleeting, Perjur'd Clarence: George Duke of Clarence (1449-78) (2ndedn. 2013; see also A.J. Pollard, ‘Richard Neville, sixteenth earl of Warwick and sixth earl of Salisbury (called the Kingmaker) (1428–1471), magnate'; M.A. Hicks, ‘George, duke of Clarence (1449–1478), prince'; A.J. Pollard, ‘Edward (Edward of Middleham), prince of Wales (1474x6–1484)'; H.Pierce, ‘Margaret Pole, suo jure countess of Salisbury (1473–1541), noblewoman', Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, www.oxforddnb.com.] As an earl of Northumberland argued c.1442, this was effectively a new earldom. [22. M.W. Warner and Kay Lacey, ‘Neville vs. Percy: A Precedence Dispute circa 1442', HR lxix (1996) 211-17] The original creation and endowment of 1337 had reverted to the crown in 1428-9.