The Certificates of Homage: Some Preliminary Thoughts

Posted by: mholford 10 years, 9 months ago

Michael Hicks explores the ceremony of homage, its surviving documentation, and possible implications for the king's relations with his tenants-in-chief.

The formalities of succession to a landed inheritance were quite complex. It was probably normally the family of the deceased or the heir who initated the writ of diem clausit extremum that instructed the escheator to hold the inquisitions that identified the heir(s), who then had to secure formal possession (seisin). A royal letter close was sent to the escheator, who normally took the new feudal tenant's fealty (oath of loyalty) - which need be taken only once regardless of how many counties where he held land. Occasionally this was delegated to another or accepted by the king himself. This however was subject to performance of homage, which was reserved to the king himself, most probably to create a profound sense of obligation in his tenants-in-chief through an impressive ceremony. It was an opportunity for the king to strike up a personal relationship with all his principal feudal tenants. Normally the taking of homage was postponed (respited) to a future date, normally a major church festival – Christmas, Easter, Michaelmas – in the not too distant future and a modest fine was exacted from the tenant for this privilege. This implies that at such festivals the royal court was swelled by tenants-in-chief performing homage to the king. Husbands of heiresses, including husbands of royal wards proving their age, did the homage that was due, providing there was issue from the union.

Respiting homage to a future date did not constitute an appointment to the tenant for an audience with the king, wherever he might be. First the tenant had to apply to the master of rolls, the senior chancery officer with custody of the inquisitions and close rolls. The master of the rolls wrote to the keeper of the privy seal to authorise the chamberlain of the king's household (who controlled access to the king) to present the tenant to the king and to certify the keeper when homage had been performed. Where the privy seal was originally applied remains visible on the certificates. The chamberlain duly endorsed the privy seal letter, sometimes with his signature, often with the statement that homage had been performed: in Latin – ‘dominus rex cepit homagium Johannis Moubray militis nunc Ducis Norfolk' ; French – ‘Le Roy ad pris son homage et voet quil eit liver'; in English - ‘the omage is take by the kyng'.[1. TNA, PSO 1/61/1; PSO 1/ 63/5, 31.] This certificate of homage constituted the authority for the privy seal office to command the issue of chancery letters close to the escheators to deliver seisin: the date given on such letters is always the same as the date of the homage.

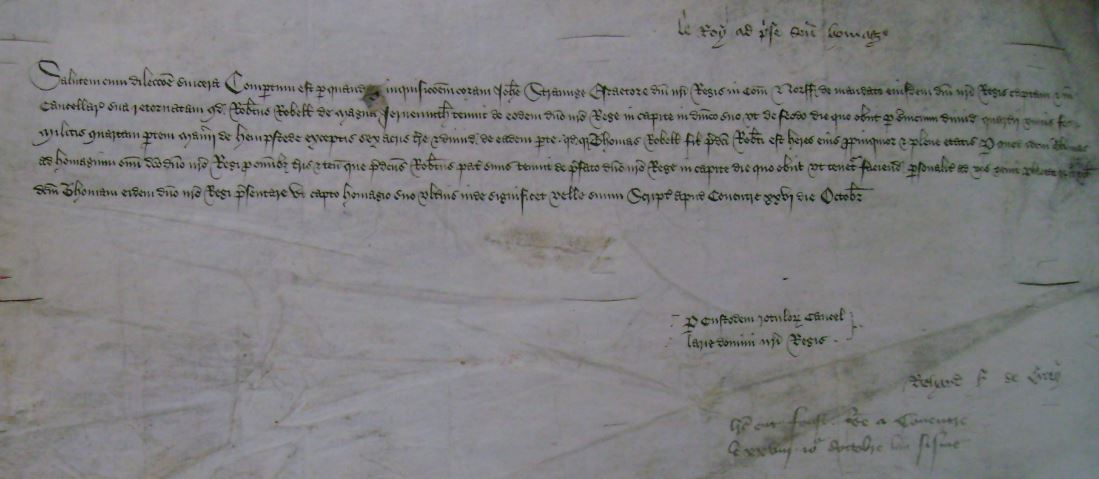

PSO 1/69/1, certificate of homage for Thomas son of Robert Robell (detail), with the signature of Richard lord Grey (d. 1418), chamberlain. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Archives.

PSO 1/69/1, certificate of homage for Thomas son of Robert Robell (detail), with the signature of Richard lord Grey (d. 1418), chamberlain. Image reproduced courtesy of the National Archives.

Like the privy seal records themselves, most of these certificates of homage are lost, but there survive four such files dating between 1350 and 1486 (mainly fifteenth-century) in The National Archives.[2. TNA, PSO 1/61-4.] Mixed in are some certificates of denization, for example of Giovanna de Giglis certified in 1483 by Francis Viscount Lovel, chamberlain of the household to Richard III.[3. TNA, PSO 1/64/54. ] A few individuals performed homage more than once for different inheritances. Most famous perhaps was the certificate of the homage of the sixteen-year-old George Duke of Clarence to his brother King Edward IV on 10 July 1466.[4. TNA, PSO 1/64/41.] Comparison with the much larger number of chancery letters enrolled on the fine and close rolls reveals that the certificates are merely a selection of what once existed, yet they cast considerably more light on the procedures and realities and on the significance of the process. All are listed in full in the TNA list, but have never been properly studied or even collated with other chancery records.

A preliminary survey indicates that the expectations in my opening paragraph were somewhat optimistic. Sometimes the tenant solicited the master of the rolls earlier – after all he wanted seisin of his inheritance as soon as possible: Reginald Lord Delawarr paid £2 for homage to be respited to Martinmas in 21 June 1428, but actually performed homage on 28 June.[5. TNA, PSO 1/62/18.] More commonly homage was overdue. Sometimes the delay was relatively trivial: thus Henry Husy's homage due at Easter 1384 was performed on 29 May and John Cressy the elder's homage due at Michaelmas 1404 was actually performed on 27 December.[6. TNA PSO 1/61/1, 7; CFR 1383-91, 253; 1399-1405, 245.] Many, perhaps most, were years overdue, like Ralph Woodford, who performed in 1459 the homage due in 1456.[7. TNA, PSO 1/64/33; CFR 1452-61, 160.] Some were much more overdue than that. William Freebody's homage, respited in 1438, was performed twelve years later, in 1450, and James Luttrell performed in 1449 the homage respited in 1437.[8. TNA, PSO 1/64/9; PSO 1/64/14.] Some individuals for whom no homage is recorded may have died before performing this essential duty. None of these had course managed without their estates in the interim and indeed in some cases seisin had been formally authorised in the writ to take fealty. In such cases it appears that the tenant felt no urgency to perform homage. There are exchequer and hanaper records relating to the prolongation of respites that remain to be investigated. At the very least, however, it appears that many of the king's tenants-in-chief took their obligation of homage rather more casually than the monarch surely wished.